10,000 miles from her native Sydney, Australia, with just $600 and a whisper of a vision, Scosha Woolridge founded a Williamsburg jewelry brand now sold in more than 125 stores worldwide

by Matt Scanlon

When Scosha Woolridge was growing up in Sydney, Australia, she spent wide stretches of time peering into dollhouses in a way she describes in retrospect as slightly different than the traditional brand of toy interaction. Her gazes, she recalled, imagined an entire world, not merely a home, and she discovered while playing that items rendered small had a strangely disproportionate power to express grand things to her.

In time, she became fascinated with art, and after studying painting and mixed-media sculpture in Australia, Woolridge was also able to begin realizing her second great passion… travel. During a four-year multinational hiking trek, which included extended jaunts in Brazil and Mexico, she began picking up regional techniques for metalworking and braiding, and it wasn’t long before she was selling jewelry designs in the sand dunes of Northern Brazil. Those extended travels were highlighted by meeting a woman from Manhattan; on a whim she traveled to the city in 2003, and found a home here that resonated far more deeply than she’d anticipated.

“I never thought of myself as a city person,” she recalled. “But I felt an immediate connection to New York.”

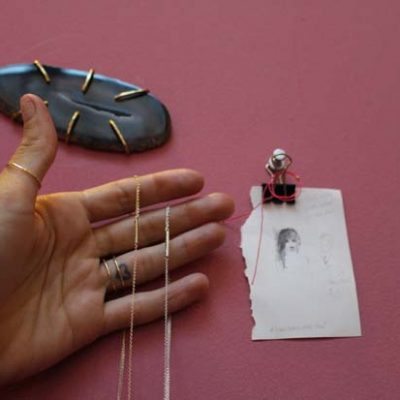

With $600, no credit, and only a small portion of her small studio to apply to the task, Woolridge started her namesake jewelry brand in 2007—her first piece’s design stemming from the memory of a young girl she met in India whose ears were freshly pierced with a “hot pink thread and accented with a single tiny gold bead,” according to her online bio. The application seemed to encompass perfect balance, and helped launched a sensibility that has remained for nearly a decade in her Williamsburg-based business—a fascination with unexpected ingredients.

Over time, the Scosha line expanded organically to include ladies, men’s, and most recently a kids and custom component (the last called Scosha Fine)—all made in the city—with an emphasis on, as she put it, being “casual, affordable, and playful.” A conversational interaction of metals, textiles, leather, and precious and semi-precious stones, the work is, as the blog Seeds and Fruit memorably put it, an investigation into “fantasy, soul, and the natural connection of things.” The brand is now sold in more than 125 department and specialty stores worldwide, and collaborates regularly with Ralph Lauren and Club Monaco on specialty pieces.

Scosha’s price line starts as modestly as $29 for an adjustable, braided ID bracelet with small brass plaque, to a newly conceived Fine line that features earrings, rings, and necklaces in the multiple thousands of dollars. There’s also a range of bespoke jewelry, which can address a great variety of individual requirements, and Woolridge was quick to detail just how fascinating an adventure that can be. Among the many daily walk-in visitors last year appeared Alexander Matisse (the great-great-grandson of legendary artist Henri Matisse) with a special request.

“His then fiancée had a beautiful ring that was given to her by her grandmother,” Woolridge recalled. “They both wanted it turned into an engagement ring, which was an amazing opportunity, but also an intimidating one. Here was this piece, charged with emotion, and we had to transform it into something else entirely. On another occasion, a woman came in with a simply amazing diamond pendant necklace that she wanted to have disassembled and re-created into other pieces. That’s a lot of work—it’s often more time consuming than simply designing from scratch, but it’s also a joy to render something truly expressive that almost transcends fashion.”

That brand of expression might not always be immediately apparent to the customer, but in Scosha’s designs, things are dependably personal. The Precious Braid Diamond bracelet, for example (photo on next page, top right)—a simple juxtaposition of braid with a precious diamond set in 10 karat gold, and among her most coveted pieces—stems from a moment in Woolridge’s travel-time.

“It’s actually meant to be an abstract portrait of a horse I came to know in Turkey,” she confided. “No one looking at the bracelet would necessarily come to this conclusion, but I think it gives the piece a special energy.”

After she took a moment to attend to a clerical matter in this frantic pre- Christmas week, the owner smiled and made mention of an artist-to-businesswoman evolution she once thought more than a little improbable.

“When I first started making jewelry, I thought, ‘My God, I’m not in the commercial world at all.’ If anything I was all about non-commercialism, and to think that after seeing poverty and orphanages…it was hard to accept that I would be making frivolous things,” she explained. “But then I did a lot of historic research on jewelry…the history of adorning ourselves, and discovered there’s a deeper meaning to why we do this.”

To Woolridge, that meaning seems to come down to identification with one’s geography and community, though she admits the definition often eludes even her.

“I just know that when I see someone connect with one of my pieces, it’s an emotional trigger for both of us, as if were tapping into something ancestral… elemental.”

Honoring jewelry making’s often distant traditions is also pivotal to the designer, and she detailed a setting range that includes styles such as Gypsy (in which stones are deeper set into precious metals, with the latter enclosing the stone in a kind of latticework) to traditional pave settings. In both styles, she often enjoys an unconventional selection of both stone type and quality.

“I certainly like traditional gems— diamond, ruby, and emerald…the classics,” she explained. “But I also like stones like turquoise that look just beautiful set into precious metal, as well as stones that are imperfect—that might have inclusions or are not the best quality. Often those seem to actually be more alive to me…more natural.”

Next year brings a few pivotal changes to the brand. A recent entry into the membership of the Council of Fashion Designers of America has engendered a slight tightening of offerings, which the designer admitted was a sometimes painful but necessary part of defining her ideology. Her higher end Fine line will be enhanced, however, and there’s also a fascinating additional project in the works.

“In part because we are made here in the U.S., we were asked to design a bracelet for the U.S. Olympic team this year,” Woolridge said. “It’s not an easy assignment; there are a lot of considerations to burrow through, but it’s An wonderful opportunity to contribute. I love that the games will be in Brazil, too, because that’s where I began making jewelry. ”

A different brand of contribution is at work in the brand’s affiliation with charities such as Circle of Health International, Women for Women International, and Every Mother Counts. The first supports relief efforts in response to the current food and energy availability crisis in Nepal and also offers worldwide relief programs, the second has given hope and support to more than 351,000 women survivors of war and conflict, while the last is a campaign to end preventable deaths caused by pregnancy and childbirth around the world. Scosha’s involvement with the groups, in the form of dedicated lines of jewelry with proceed-directed revenue, is part of a mission of providing an “authentic point of view of environmental, social, and personal awareness.”

“At the end of the day, we are here for each other,” Woolridge offered, “and recognize that there is a far more resonant kind of accounting that needs to be engaged in.”

Scosha

64 Grand Street / 718.387.4618 / scosha.com